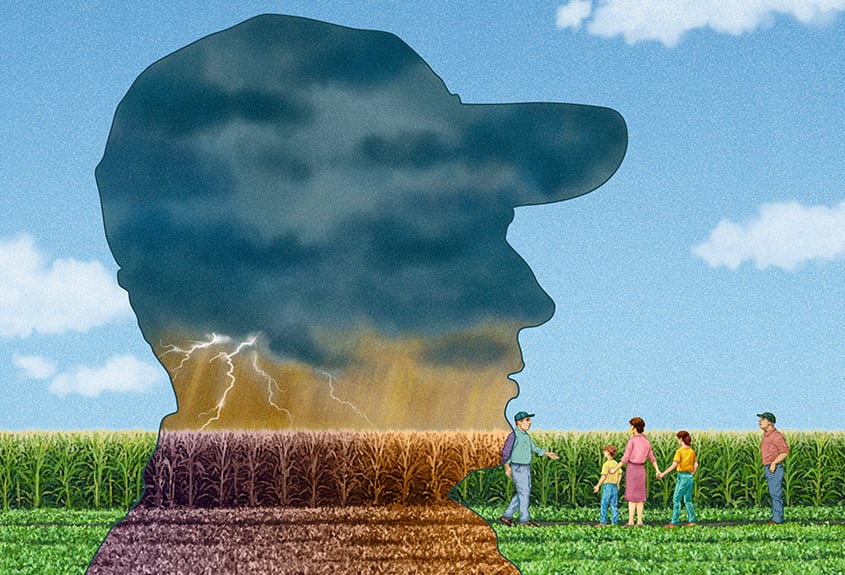

Bringing Mental Health Out of the Darkness

Agriculture is finally talking about mental wellness on the farm — a topic once shrouded in silence and shame.

Learn how you can help your #ag community when it comes to addressing mental wellness.

Depression and anxiety on the farm are pressing problems that have long simmered in relative secrecy with little attention or open discussion. Shelby Watson-Hampton knows this too well; her older brother, Russ, who almost always appeared outgoing and energetic, silently battled depression and anxiety. Suicide claimed his life in 2003. Watson-Hampton farms in Maryland with her family on their fourth-generation family farm, Robin Hill Farm & Vineyards.

click to tweet ![]()

“Suicide was very stigmatized then. It just wasn’t talked about,” she says. “So I think we did what a lot of farm families do: We just shut down a little bit.”

In fact, the issues of anxiety and depression have been — and continue to be — widespread in ag. High percentages of farmers and farmworkers say financial issues (91%), farm or business problems (88%) and fear of losing the farm (87%) impact their mental health, according to a 2019 poll sponsored by the American Farm Bureau Federation. They just haven’t been talking about it. “Rural people take pride in taking care of themselves and handling situations,” says Ted Matthews, director of Minnesota Rural Mental Health. “That positive thing can become a negative when they need help and they have too much pride to ask for it. That happens far, far too often. Farmers will say, ‘I can still handle this.’ And my question is, ‘Why?’ If you can feel better, why wouldn’t you? We can only handle so much. The problem is, none of us knows how much that is.”Suicide was very stigmatized then. It just wasn’t talked about. So I think we did what a lot of farm families do: We just shut down a little bit.

Signs of Trouble

When it comes to warning signs of depression and anxiety — whether in yourself or someone else — David Merrell, M.D., says one of the main things to look for is a loss of enjoyment. “You stop doing the things that you enjoy doing — the activities, the fishing, whatever it is,” says Merrell, the on-site medical doctor for Syngenta in Greensboro, North Carolina. “Individuals who are starting to face depression and anxiety find there’s a mounting weight on them that makes those activities no longer enjoyable.”

Weight gain or weight loss can be another sign, as is increased emotionality, such as becoming tearful over simple interactions. “Maybe deadlines are being missed where they never used to be missed — fields aren’t getting planted when they used to,” Merrell says.

Marriage issues and alcohol or opioid abuse also can be symptoms, and Matthews often hears about people isolating themselves, withdrawing from family and friends. “People start talking less and less, and they’re left to their own thoughts. They feel alone.”

Additional signs indicating that a person might need help include:

- Decline in care of crops, animals and farm

- Deterioration of personal appearance

- Buying more life insurance

- Increase in physical complaints, difficulty sleeping

- Giving away prized possessions

- Making statements such as “I have nothing to live for” and “My family would be better off without me.”

Giving and Getting Help

Many experts suggest that listening nonjudgmentally, with care and concern, is often the most effective way people can help someone facing anxiety or depression. “Communication is hugely important, but you have to learn how important it is by actually doing it,” Matthews says. If someone in your life needs to talk, be sure to listen — don’t blame, he adds. “No two people are alike, so you can’t say, ‘Why can’t this person handle this?’”

Like many problems, it “takes a village” to help solve the mental health crisis in rural America. “All of us in rural communities are in this together,” Matthews says. “If people don't know what to do, they do nothing. More medical doctors and psychologists would be helpful. But without community involvement, little progress will be made.”

For the person suffering from depression, proactively finding that kind of support system is crucial, Merrell says. “This I cannot stress enough: Find somebody you can confide in to say, ‘I’m having a hard time,’" he says. “That person might be a friend, a spouse, a clergy member or a mental health professional who will be able to give you tools and say, ‘Hey, next time this comes up, here’s what you’ve got to do.’”

These conversations don’t always require going into an office. “There are a lot of telehealth opportunities so you can seek help from professionals over the phone,” Merrell notes.

Today, there are more outlets for help and more awareness than ever before. “It is really refreshing, in the last five years, to see that a lot of groups in the ag community have realized mental health can be a real problem,” Watson-Hampton says. “Major land grant universities, extension agencies, commodity groups, agribusinesses — they’re all looking at it now. It comes up at almost every ag conference I’ve gone to in the last year or two, which is a huge change. There are farm crisis centers and farm resources like Farm Town Strong, which is a collaboration of the Farm Bureau Federation and National Farmers Union to combat opioid addiction.”

This greater acceptance of mental health issues has helped lift the stigma she felt after her brother’s death and has brought the issues into the light. “We all struggle with something,” Watson-Hampton says. “Mental health, just like physical health, is a part of our overall well-being, and it needs attention sometimes. It’s so much better to be fully functioning, healthy and alive than it is to fight this dark battle on your own or to give into it. There are so many opportunities for help, and needing it is so normal.”

Resources

To get mental health counseling or to learn more about mental health issues, contact these organizations:

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

- Employee Assistance Program

- Make It OK

- National Alliance on Mental Health

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 1-800-273-8255

- Ted Matthews