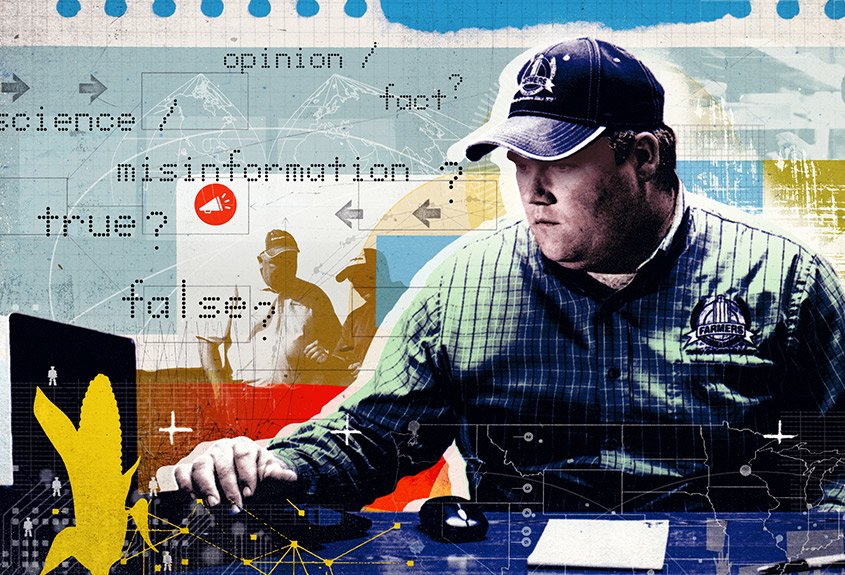

Weigh the Evidence When Assessing Scientific Claims

Experts share advice on drinking from the information firehose available to growers.

Q. What sources do you find the most helpful for evaluating new ag technology?

A. David Zaruk, Ph.D., professor of communications and marketing at Odisee University College in Brussels, environmental health policy risk analyst at Risk Perception Management: Farmers. If a technology works, they will demand it again. If it doesn’t, they will not waste their money the next season. Researchers need to work closely with farmers, especially those with a pioneering spirit who are actively working for a better, more sustainable means to harvest.

A. Tim Pastoor, Ph.D., president of the Health & Environmental Sciences Institute, founder of Pastoor Science Communications, LLC: Go to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or the Food and Drug Administration; they are qualified, and they are the referees in these situations. You need a referee because if you left it to the players, there would be a considerable amount of bias in every single call. Those government agencies have access to all the relevant facts and must come to an objective decision that’s in the best interest of everyone.

A. Zaruk: A lot of times, they can’t. Before the internet revolution, studies were published and debated before science communicators conveyed the information to the public. Most news organizations no longer have science editors. This means consumers are “doing their own research,” which generally is simply confirming their own biases. Objective, quality research rarely has the support to reach the public, but it does still exist, and critically thinking consumers can pick it out if they’re looking.

A. Pastoor: I accept and expect some level of bias in everything. That’s human nature. It’s too easy to say, “Hey, you’re biased. I’m not.” Bias is about our individual perspectives and context. The same data can be interpreted and cast in many different lights. But I try to triangulate information against three pillars: First, I look at the opinion in terms of the speaker’s qualifications. Is this person an expert? What makes him or her an expert? Ask your doctor for an opinion on health, and you’ll get expert advice. Ask your doctor about climate change, and you might get an opinion that isn’t much better than your own. Second, accept that this person has biases, but seek out their objectivity. If an opinion is objectively supported by facts, I can be OK with that, even when I disagree with the interpretation. Lastly, I look for other opinions to find a consensus viewpoint. If several experts express the same or similar viewpoints, that strengthens the conclusion.

Q. The information flow is a raging river these days. How can retailers and farmers find information relevant to their operations?

A. Zaruk: Unfortunately, there is often poor communication and coordination between researchers, ag retailers and farmers, which also extends to food processors, manufacturers, brands and consumers. Participants up and down the agricultural supply chain need to make sure they share new information with each other as it becomes available, because what is relevant to one is also relevant to their industry partners.

A. Pastoor: We have a human tendency to believe what we want to believe. But if you’re sincerely interested in learning and forming a solid perspective, use this three-step process: consensus, qualifications and objectivity. When reading an article, wherever it happens to be, ask yourself, “Is it referencing consensus information from qualified sources that try for objectivity?” It needs to check those boxes. Avoid yoga teachers opining about pesticides while trying to sell their own dietary supplements. Do go to the EPA website and look for fact sheets and FAQ that can help you form your opinions.

Q. When we see inaccurate information on social media, is there a strategy that can help change the perception?

A. Zaruk: It seems that more and more, social media is becoming a divisive world of echo chambers with limited levels of stakeholder dialogue. Public trust is eroded when even the experts are seen attacking and silencing those who may disagree. The first point in any strategy is to engage openly, professionally and calmly; it is not about winning each argument for the sake of winning the argument, but about developing public trust.

A. Pastoor: It’s important to take a deep breath and decide if engaging would make a difference. Walk away from extreme positions. Onlookers may see you as the same. If you decide to engage, ask for or state facts and qualifications, and look for objectivity, especially in yourself. Cool headedness often starts with opening our ears before opening our mouths, then engaging in factual discussion and civil debate.

A. David Zaruk, Ph.D., professor of communications and marketing at Odisee University College in Brussels, environmental health policy risk analyst at Risk Perception Management: Farmers. If a technology works, they will demand it again. If it doesn’t, they will not waste their money the next season. Researchers need to work closely with farmers, especially those with a pioneering spirit who are actively working for a better, more sustainable means to harvest.

A. Tim Pastoor, Ph.D., president of the Health & Environmental Sciences Institute, founder of Pastoor Science Communications, LLC: Go to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or the Food and Drug Administration; they are qualified, and they are the referees in these situations. You need a referee because if you left it to the players, there would be a considerable amount of bias in every single call. Those government agencies have access to all the relevant facts and must come to an objective decision that’s in the best interest of everyone.

Q. How can ag consumers determine bias in a study?Participants up and down the agricultural supply chain need to make sure they share new information with each other as it becomes available, because what is relevant to one is also relevant to their industry partners.

A. Zaruk: A lot of times, they can’t. Before the internet revolution, studies were published and debated before science communicators conveyed the information to the public. Most news organizations no longer have science editors. This means consumers are “doing their own research,” which generally is simply confirming their own biases. Objective, quality research rarely has the support to reach the public, but it does still exist, and critically thinking consumers can pick it out if they’re looking.

A. Pastoor: I accept and expect some level of bias in everything. That’s human nature. It’s too easy to say, “Hey, you’re biased. I’m not.” Bias is about our individual perspectives and context. The same data can be interpreted and cast in many different lights. But I try to triangulate information against three pillars: First, I look at the opinion in terms of the speaker’s qualifications. Is this person an expert? What makes him or her an expert? Ask your doctor for an opinion on health, and you’ll get expert advice. Ask your doctor about climate change, and you might get an opinion that isn’t much better than your own. Second, accept that this person has biases, but seek out their objectivity. If an opinion is objectively supported by facts, I can be OK with that, even when I disagree with the interpretation. Lastly, I look for other opinions to find a consensus viewpoint. If several experts express the same or similar viewpoints, that strengthens the conclusion.

Q. The information flow is a raging river these days. How can retailers and farmers find information relevant to their operations?

A. Zaruk: Unfortunately, there is often poor communication and coordination between researchers, ag retailers and farmers, which also extends to food processors, manufacturers, brands and consumers. Participants up and down the agricultural supply chain need to make sure they share new information with each other as it becomes available, because what is relevant to one is also relevant to their industry partners.

A. Pastoor: We have a human tendency to believe what we want to believe. But if you’re sincerely interested in learning and forming a solid perspective, use this three-step process: consensus, qualifications and objectivity. When reading an article, wherever it happens to be, ask yourself, “Is it referencing consensus information from qualified sources that try for objectivity?” It needs to check those boxes. Avoid yoga teachers opining about pesticides while trying to sell their own dietary supplements. Do go to the EPA website and look for fact sheets and FAQ that can help you form your opinions.

Q. When we see inaccurate information on social media, is there a strategy that can help change the perception?

A. Zaruk: It seems that more and more, social media is becoming a divisive world of echo chambers with limited levels of stakeholder dialogue. Public trust is eroded when even the experts are seen attacking and silencing those who may disagree. The first point in any strategy is to engage openly, professionally and calmly; it is not about winning each argument for the sake of winning the argument, but about developing public trust.

A. Pastoor: It’s important to take a deep breath and decide if engaging would make a difference. Walk away from extreme positions. Onlookers may see you as the same. If you decide to engage, ask for or state facts and qualifications, and look for objectivity, especially in yourself. Cool headedness often starts with opening our ears before opening our mouths, then engaging in factual discussion and civil debate.

Always weigh the evidence. Our experts share their advice on assessing the wealth of information available to #growers.

click to tweet ![]()